Flung into a different universe, Jake looks around, amazed by wonders of the alien world around him. An array of seemingly unnatural colours grow and glow from the darkness. As he floats through this new environment, he is filled with a sense of excitement and his brain works to process the spectacle before him.

No. This isn’t a scene from Avatar. He’s def not in a groovy black-lit basement. Jake has just taken his first UV night dive off the coast of Gili Meno.

UV diving is a form of night diving that is more correctly called “Fluorescent” or “Fluoro” diving. The light used to reveal the splendid, neon colours is actually not ultraviolet (which is invisible to the human eye) but a blue light with a wavelength of around 470nm (if you’re interested in that kind of thanggg….). When exposed to this blue ‘excitation light’, scientists have found that some corals glow in hues of yellow, green and orange. Different from bioluminesence, fluorescent corals do not emit their own light. Instead, they take the light in, get a little crazy with some electrons, and then re-emit the light with a different wavelength.

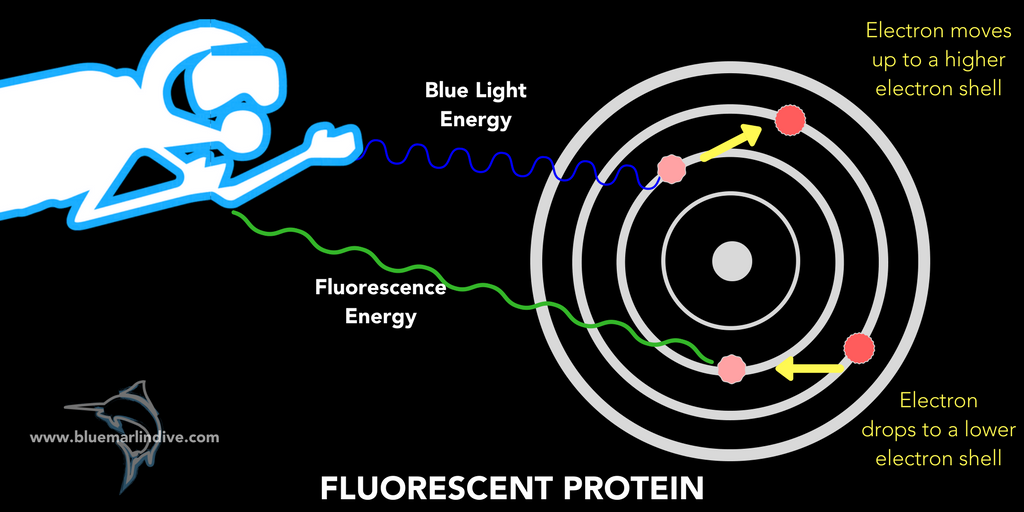

Oh you want more? No problem, Madame Curie. Okay, more specifically, fluorescent animals contain proteins that absorb the energy from the blue light. The energy from the blue lights boosts electrons within these specified proteins into a more energetic but very unstable state, jumping from valance electron shell to a higher shell. The electrons then immediately return to a more stable state, emitting the excess energy as light of a longer wavelength and lower energy, typically displaying in greens, yellows, oranges and reds. The colour that we eventually see is based on how many jumps the electron makes.

While the presence of fluorescence in marine creatures has been known to scientists for almost 100 years, getting to see creatures in this environment has only been available to the public in the past 10 years. Now, increasingly advanced technology has made this world more readily available and we continue to learn more about fluoresence. Whilst studying and filming fluorescent corals in 2013, one scientist noticed an aberration on one of his films. He suspected foul play – was one of his colleagues playing a practical joke? No! It was a little moray eel, lit up like an orange glow stick. Since then, over 200 fish species have been found to fluoresce, and in 2015 the first glowing reptile was discovered (a population of hawksbill turtles in the Solomon Islands).

The exact reasons why fluorescence has evolved in so many disparate species remain unclear, but it is not surprising that organisms living in a predominantly blue world will make use of that blueness.

Fluorescence may have developed in corals as a form of sun protection allowing organisms to absorb and release excess UV energy. Some corals’ body mass are comprised of up to 17% of these special proteins, so they are clearly important in some way.

For many glowing fish, intraspecies recognition seems to be the main advantage; i.e. to help members of the same species identify each other. As many of these species have yellow filters in their eyes that allow them to see bioflouresence in others, it is possible the glow is used to communicate while remaining hidden from predators. I mean, if you are a small eel and spend much of your life hiding away in nooks and crannies, you don’t want to spend too much time out and about looking for a mate. It helps if you can sneak out into the open, spot a glowing partner, do the deed and then return quickly to the safety of your hidey hole. A little like Underwater Tinder.

Some animals use it to differentiate between species. For example, in white light different species of lizardfish are almost indistinguishable. However, under the blue light, they glow with different patterns.

For other creatures, fluorescence is a camouflage rather than a signal. Monocled bream have glowing stripes on their head that help them blend in amongst glowing staghorn corals, and pink-glowing scorpionfish are often found sitting on reddish-glowing algaes and sponges.

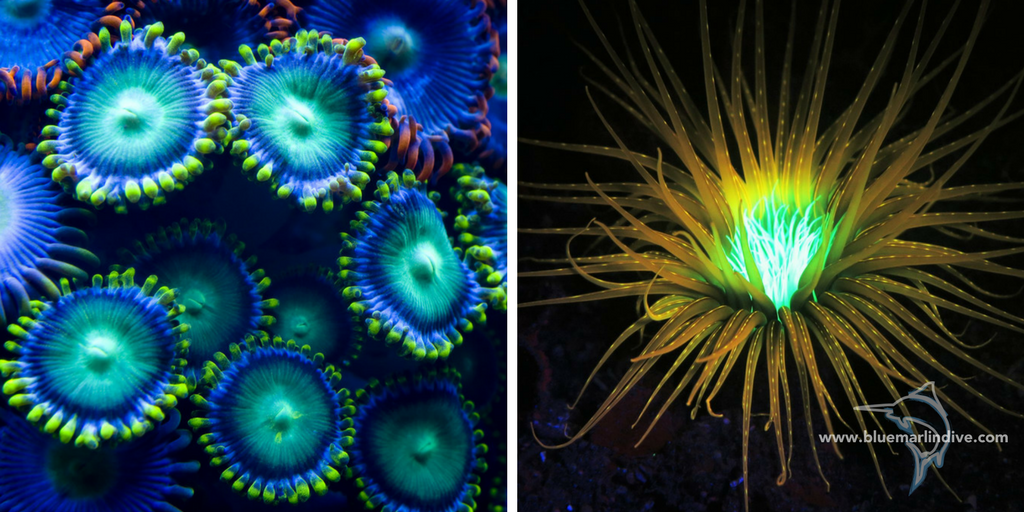

Other organisms may use their light as a lure (much as many deep sea organisms employ their bioluminescence). Banded coral shrimps at first glance appear not to glow, but upon closer inspection their chests and the tips of their pincers glow. Tube anemones have illuminated tentacles and mouthparts.

And, as ever, in the evolutionary arms race, there are always predators seeking to exploit any advantage they can. Several predatory fish species have natural yellow filters on their eyes to help them seek out glowing prey.

Just as underwater organisms have learned to use the biofluorescence, so have scientists. UV or fluoro diving has become an indispensable tool for those who study and work to conserve coral reefs with many researchers using the blue light as a way to help judge the health of reef systems. In the white light of day, scientists can notice more obvious changes, but the blue light reveals much more than is visible to the naked eye. Many reef destroying algae that are invisible in the light of day glow red under the blue light. Dying sections of coral that may appear fairly healthy during the day have little or no color, signifying the beginning of a problem.

But what does this all mean for you? Well, let’s walk through it. We equip each diver with a blue excitation light as well as a yellow filter on each mask that enhances the fluorescent light of the animals as well as protecting your eyes from the harsh blue light. Of course, cutting out much of the ambient light means the rest of the reef will look much darker than normal. This is why we want you to be comfortable with normal night diving and have good buoyancy skills before coming on a UV dive.

You start the dive the same way you would a normal night dive. Gearing up begins right before dusk so that we can enter the water just as it gets dark. Those who may not want to jump into the pitch black ocean: don’t fret! We arm each diver with a normal dive torch to help calm the nerves! Once you get settled, though, switch that light off and plunge yourself into darkness. Once you turn on your blue light, the show begins.

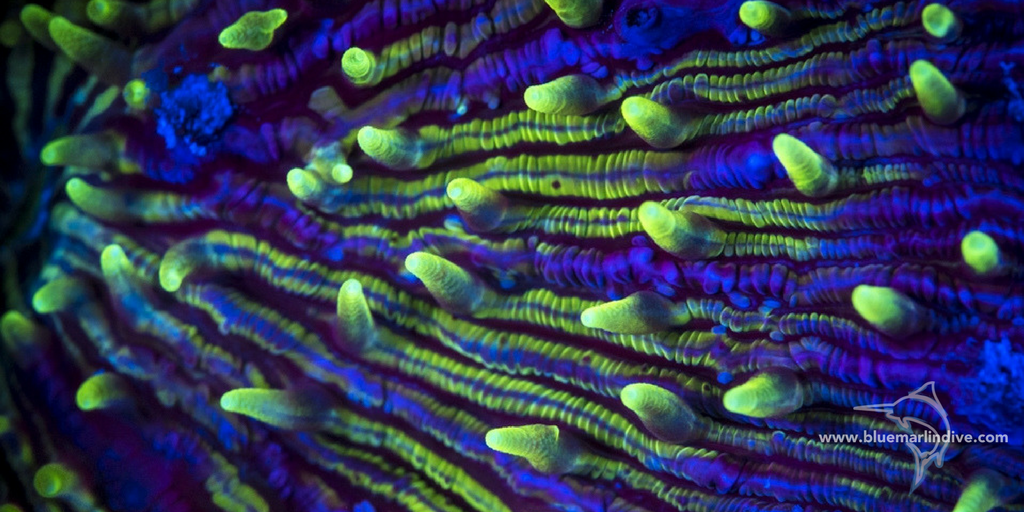

In some locations entire reefs light up like a psychedelic trip, but here in the Gilis your fluoro experience is more of a treasure hunt. Patches of coral light up in shades of green/yellow, and because corals are so much more active at night than during the day, you can see the structure of each polyp clearly enhanced by the glow. Under a blue light the corals really appear to come to life and you’ll look at them with new eyes.

Between the corals, tiny anemones dot the ground like stars. Orange eyes peer up from the sand where their owner lies buried. We have glowing crabs carrying glowing anemones on their carapaces, scorpionfish, bream, eels and lizardfish. Miniscule gobies gleam pink and blue against the faint reddish backdrop of a sponge and whilst we have yet to find a hawksbill at night, our green turtles have a faint but distinct glow around the edge of their shells. Once, divers were even treated to a glowing parasitic louse on a non-glowing damsel! As this is still such a new discipline every dive is a voyage of discovery.